On the eve of last week's presidential debate, Republican Mitt Romney floated a trial balloon to deflect public attention from his detail-free tax plan certain to give a massive windfall for the wealthy, burden middle class taxpayers and balloon the national debt. But largely overlooked in his murky and still-to-be defined proposal to put a dollar cap on individual tax deductions is the devastating impact it would have on charitable giving. Combined with his demand to end the estate tax, Romney's plan would choke off donations to America's non-profits, churches and charities.

When President Obama in 2009 proposed raising $318 billion over the next decade by trimming wealthier taxpayers' deductions for charitable giving from 35to 28 percent, Republicans were apoplectic. Then House Minority Leader John Boehner darkly warned the reform would "deliver a sharp blow to charities at a time when they are hurting during the economic downturn." But as Bloomberg and The Chronicle of Philanthropy each explained at the time, Obama's proposal would likely have little to no impact on charitable giving. An analysis by the Center on Budget and Policy put the impact at only 1.9 percent of total donations. Noting that the same upper income 28 percent deduction was in place during Ronald Reagan's first term, then-OMB chief Peter Orszag rightly concluded that "what drives charitable contributions is overall economic growth."

But Governor Romney's proposed cap on individual deductions is another matter altogether. As he explained his new plan conveniently unveiled on the eve of last week's first presidential debate:

"As an option you could say everybody's going to get up to a $17,000 deduction; and you could use your charitable deduction, your home mortgage deduction, or others - your healthcare deduction. And you can fill that bucket, if you will, that $17,000 bucket that way. And higher income people might have a lower number."

Within 24 hours, Romney changed his plan yet again. Once-again side-stepping the question of which tax credits, deductions and loopholes he would end, Romney pulled a new figure out of the air during Wednesday's debate:

"Make up a number, $25,000, $50,000. Anybody can have deductions up to that amount. And then that number disappears for high-income people."

If so, a large source of funding for America's hospitals, museums, institutions of higher education and more might disappear as well.

Currently, only about 30 percent of filers itemize their deductions, which in 2009 averaged over $26,000. But as Ezra Klein explained last week, "80 percent of tax savings from itemization goes to the top 20 percent of Americans households, and 25 percent of the savings goes to the 1 percent." In 2011, the Congressional Budget Office said those making over $500,000 a year gave 3.4 percent of their income to charity. (Individual contributions accounted for $227 billion of the $304 billion raised by charities in 2009.) Romney's proposed cap would have its greatest impact on upper-income, blue state residents, whose larger state and local tax bills and home mortgage interest payments currently provide the biggest sources of deductions. But charitable giving by the wealthiest Americans, like Mitt Romney's own $2.25 million deduction in 2011, could be slashed as well.

Jim Andreoni, a UC San Diego professor of economics who studies the economics of charitable giving, explained why:

"The effect on charitable giving is likely to be large for high income individuals, especially in the short run..."Some deductions are difficult to change, like mortgage interest or property taxes," says Andreoni. "Those will stay fixed for now, and for many high earners will more than use up the $17,000 cap on deductions. By contrast, charitable giving is about the only category of deduction that people can use in the short run to adjust for an increase in taxes. ... [E]ven though both your mortgage and your charitable giving are losing some tax benefits, only your giving can change in the short run to make up part of that loss.

So, high income donors will have two reasons to cut back on giving. First, they are losing after-tax income from deductions on things other than giving and that are hard to adjust, like mortgage interest. Second, giving itself will become far more expensive and is far easier to change than other deductions. It's intuitive to me that charitable giving will take a big hit from the cap on deductions."

(Given his annual 10 percent tithe mandated by his church, Mitt Romney would likely be an exception to the rule. Still, that doesn't make his claim that his charitable contributions make his own paltry tax rate "really closer to 45 or 50 percent" any more true.)

But capping the dollar value of annual deductions isn't the only way Mitt Romney's tax plan would gut charitable giving. As it turns out, Romney's proposal to end the estate tax, a move which would save his heirs $80 million and those of his billionaire backers billions more, would dramatically slow the cash flow to America's non-profits.

In 2003, the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center documented the hemorrhaging that would ensue. As the TPC described, "The estate tax encourages charitable giving at death by allowing a deduction for charitable bequests" and "also encourages giving during life." Its repeal would be devastating for U.S. charities:

We find that estate tax repeal would reduce charitable bequests by between 22 and 37 percent, or between $3.6 billion and $6 billion per year. Previous studies are consistent with this finding, and also imply that repeal would reduce giving during life by a similar magnitude in dollar terms. To put this in perspective, a reduction in annual charitable donations in life and at death of $10 billion due to estate tax repeal implies that, each year, the nonprofit sector would lose resources equivalent to the total grants currently made by the largest 110 foundations in the United States.1 The qualitative conclusion that repeal would significantly reduce giving holds even if repeal raises aggregate pre-tax wealth and income by plausible amounts.

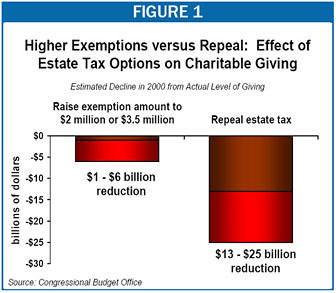

That finding was echoed the next year by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Ironically, its director then was Douglas Holtz-Eakin, who later served as the chief economic advisor to Republcian presidential candidate John McCain. (Even more ironic, McCain called for the repeal of the estate tax in 2008, despite two years earlier having proclaimed "most great civilized countries have an income tax and an inheritance tax" and "in my judgment both should be part of our system of federal taxation.") As CBO director Holtz-Eakin wrote in "The Estate Tax and Charitable Giving":

Furthermore, the estate tax provides an incentive to make charitable contributions during life. The paper finds that increasing the amount exempted from the estate tax from $675,000 to either $2 million or $3.5 million would reduce charitable giving by less than 3 percent. However, repealing the tax would have a larger impact, decreasing donations to charity by 6 percent to 12 percent.

In 2006, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) provided a sobering assessment of what proposed estate tax reforms would do to philanthropy among the wealthiest Americans. Whether the estate tax was repealed outright, the size of the exempted assets raised or the tax rate itself dropped, American charities would suffer painful losses of funding:

- CBO estimated that, had the estate tax not existed in 2000, charitable donations would have been $13 billion to $25 billion lower that year. CBO found that repealing the estate tax would have reduced charitable bequests by 16 to 28 percent and charitable giving during life by 6 to 11 percent.

- The amount by which CBO found that charitable donations would have fallen in 2000 exceeds the total amount of corporate charitable donations in the United States in that year (which equaled $11 billion) and approaches the total amount that foundations contributed to charitable causes ($25 billion).

- A study by Brookings Institution economists Jon Bakija and William Gale found effects of similar magnitude, as have analyses by various other researchers.

Now, it is entirely possible that Romney may exempt charitable giving from his as-yet-to-be fleshed out cap. As Romney aide and Bush Florida recount lawyer Ben Ginsburg claimed last week, "You pay for the tax cuts in the way that Governor Romney is going to articulate in the next five weeks. You are going to hear that from his mouth in the coming days." Or then again, you may not. As GOP strategist Michael Murphy (the same Michael Murphy who said in 2005 that Mitt Romney has "been a pro-life Mormon faking it as pro-choice friendly") put it on Sunday's Meet the Press:

"Here is the problem. You guys won't give him any credit for closing loopholes, because like you guys, he won't name the loopholes. Why? Because you'll attack him for doing it. You attack him for not giving you a little target... and then you attack him when you get the target."

To put it another way, Mitt Romney's smokescreen surrounding his tax plan his political cowardice, pure and simple. And that is being charitable.