By Jeff Gerth, ProPublica

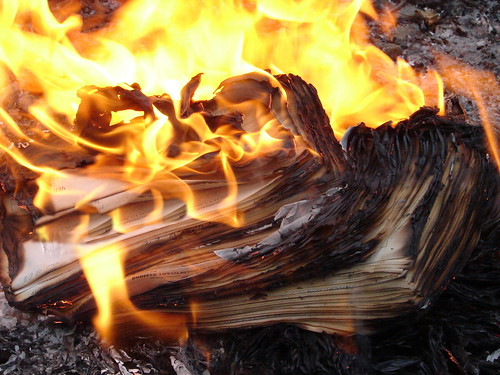

In 1994, a scientist studying her company's new medical imaging dye reached troubling findings. Her boss, she recalls, told her to "burn the data."

That alleged request surfaced this week in a groundbreaking trial over the dye, which is injected into patients to sharpen MRI scans and has been owned since 2004 by GE Healthcare. At issue is whether GE did enough to protect patients from a rare but devastating side effect of the dye: a disease that causes large areas of the skin to become thick and hard. ProPublica investigated the dye in 2009 and 2010, revealing that GE ignored the advice of its own safety experts to "proactively" restrict its use.

GE's lawyer, John Fitzpatrick, didn't dispute the request to burn the data in his opening statement to the jury on Tuesday. But after this story was published, the company told ProPublica that the scientist's boss denies having told her to destroy data. Fitzgerald also confirmed that an outside researcher will testify that he would not have published a study stating the dye was safe if he had been shown certain internal company research.

But Fitzpatrick insisted that GE's accusers were twisting such evidence to falsely impugn the company and wrongly suggest that it had endangered patients. He insisted GE had always acted ethically with regard to the dye, known as Omniscan.

After settling several hundred other cases out of court over the last several years, GE went to trial this week in federal court in Cleveland — the first opportunity for the drug's history to be fully aired. The plaintiff, Paul Decker, 61, contends that he contracted the skin ailment, known as nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, because of an injection of Omniscan in 2005. He was diagnosed in 2010.

His lawyer, Christopher Tisi, told jurors that Decker's skin feels like wood or granite, and that he "has a really hard time doing most anything." Tisi asked the jury to hold GE accountable for repeatedly ignoring the drug's problems by returning a verdict of more than $12 million.

Fitzpatrick maintained that GE and predecessor companies that sold Omniscan did all they could to ensure the safety of what he said was a "wonderful product" that had "saved millions of lives." GE also issued a statement to ProPublica defending its actions and emphasizing the benefits of Omniscan.

So-called contrast agents such as Omniscan help radiologists obtain sharper images from MRI scans. The agents contain a toxic metal, gadolinium, but they are bonded with a protective coating to keep the gadolinium inert. The drug is normally filtered out through the kidneys without causing any harm. The skin ailment — which can also stiffen internal organs such as the heart and lungs, causing death — has mainly been confined to patients with kidney disease, which Decker suffered from.

GE Healthcare acquired Omniscan in 2004 when it purchased a U.K. company. The first association between Omniscan and the skin disease was disclosed in 2006.

In 2010, the FDA banned the use of Omniscan and two other contrast agents in patients with severe kidney disease. There have been no new cases of the skin disease in recent years.

The heart of the dispute is whether GE hid Omniscan's problems.

Tisi argued that internal studies decades ago showed problems, putting up a "big yellow light." But the company that then owned the dye, he said, went "forward fast" to put it on the market. The drug was approved for sale in the U.S. in 1993. Fitzpatrick said the company's research submitted to the FDA was the "gold standard."

Later, Tisi went on, one company researcher, Karen Saebo, was told to "burn the data" because the results were not favorable and would need to be submitted to the FDA.

Fitzpatrick countered that Saebo never destroyed her data and, in fact, turned in her report. In earlier testimony, which was shown by video to the jury on Wednesday, Saebo said that the alleged request by her boss left her "terrified" that she would be fired. Still, she did not follow the directive and retained the data.

After this story was published, a GE spokesperson sent an email to ProPublica stating that "the manager clearly denies that Dr. Saebo was ever told to burn data" and that it was the manager "who properly saved and produced this information."

Fitzpatrick acknowledged that another research report done for the company had not been disclosed, but he argued that it had no clinical significance. "The evidence will be that we didn't hide a thing," except for not submitting two rat studies, he said. GE, Fitzpatrick argued, had always been "ethical and responsible" in warning about the dye's problems.

Tisi had another example for the jury: a study done for the company that owned the dye in the 1990s.

For that study, researchers collected all the gadolinium excreted through the kidneys. But after three weeks they were still missing about 25 percent of the gadolinium that had been injected into the body. The company reassured the researchers that there was nothing to worry about, Tisi said, and that the missing gadolinium had been sweated out.

The researchers went ahead and published their study, which concluded that Omniscan was safe and effective. But, the lawyer for Decker said, the authors later withdrew their paper after learning that they had not been shown "secret studies" revealing some of Omniscan's problems, such as an animal study showing skin changes.

Fitzpatrick, in response, acknowledged that one of the authors will tell the court he would not have published the study had he seen an animal study. But the GE lawyer also said that the missing gadolinium was "no secret" and that the scientist did not disavow his fundamental finding that the drug was safe for the patient.

Another point of contention is whether Omniscan's owners acted properly when serious problems in patients first began to emerge in the early 2000s.

Tisi acknowledged that those cases were not known at the time to be the debilitating skin disease, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, or NSF, that his client suffers from. But he maintained that those early cases were severe enough to have prompted significant action, such as changing the label or reformulating the drug to make it safer.

A label warning about the disease was not added until 2007, after the FDA pressed all makers of gadolinium-based imaging dyes to highlight the risk to patients with kidney disease.

Fitzpatrick said that at the time of Decker's MRI scan in 2005, months before the link between contrast agents and the disease was first disclosed in 2006, the company was already warning doctors of possible side effects. The package insert noted that "caution should be exercised in patients with renal impairment." Tisi said that was not enough.

In pretrial motions, presiding judge Dan Aaron Polster has barred or limited some of GE's scientific testimony concerning the causes of NSF, which the company maintains has not been conclusively shown to be caused by Omniscan. The manual used by radiologists says that exposure to gadolinium contrast agents is a necessary factor in the development of the disease.

Judge Polster also denied Decker's attempt to recover punitive damages.