The Affordable Care Act is working. 2.5 million more young adults ages 19 to 26 now have health insurance. The shrinking of the Medicare "donut hole" allowed 3.6 million seniors to save $2.1 billion on their prescription drugs last year. And the ban on insurers refusing to cover pre-existing conditions is saving lives (even among those who opposed so-called "Obamacare"). And even though most of its provisions don't go into effect until 2014, the data from Oregon and Massachusetts strongly suggest the 30 million people who will gain coverage will be much healthier and more financially secure.

In Massachusetts, the 2006 health care reform Governor Mitt Romney signed into law lowered the uninsured rate from 10 percent to a national low of two percent. Even with its individual mandate, "Romneycare" is extremely popular, enjoying a 3 to 1 margin of support from Bay State residents. Now, a new study by Charles J. Courtemanche and Daniela Zapata published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBR) shows that universal coverage in Massachusetts is indeed making people there healthier. As Ezra Klein of the Washington Post summed up their findings:

The answer, which relies on self-reported health data, suggests they did. The authors document improvements in "physical health, mental health, functional limitations, joint disorders, body mass index, and moderate physical activity." The gains were greatest for "women, minorities, near-elderly adults, and those with incomes low enough to qualify for the law's subsidies."

Importantly, the researchers concluded that "the general strategies for obtaining nearly universal coverage in both the Massachusetts and federal laws involved the same three-pronged approach of non-group insurance market reforms, subsidies, and mandates, suggesting that the health effects should be broadly similar." (Or MIT professor and architect of both laws Jonathan Gruber put it bluntly last year, "they're the same f--king bill.") It's no wonder Mitt Romney used to recommend his Massachusetts reform as a model for the nation.

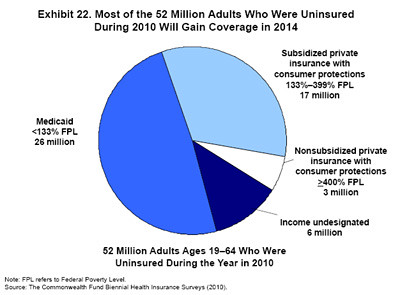

If the individual mandate is one of the highest profile (if contentious) aspects of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, the expansion of Medicaid is among the most important in enabling 30 million currently uninsured Americans to get coverage. By extending Medicaid coverage to families earning up to 133 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) and providing subsidies to those up to four times the FPL, starting in 2014 the Affordable Care Act passed by Democrats in Congress will bring insurance to millions more Americans. A March 2011 analysis by the Commonwealth Fund revealed that when fully implemented, the ACA will bring relief to "nearly all of the 52 million working-age adults who were without health insurance for a time in 2010."

As it turns out, America's future is Oregon's present.

That's the word from another study released last fall by the NBER. The same nonpartisan group that determines the official beginning and end of recessions, NBER found, as Harvard researcher and former member of President George W. Bush's Council of Economic Advisers Katherine Baicker put it, "Medicaid matters."

The NBER study avoided the pitfalls of past studies by examining the case of Oregon. After Oregon in 2008 established a lottery to add 10,000 people to its limited Medicaid rolls, the NBER team interviewed 6,000 of the lucky ones and 6,000 of the 90,000 who lost out. The results were striking:

We find that in this first year, the treatment group had substantively and statistically significantly higher health care utilization (including primary and preventive care as well as hospitalizations), lower out-of-pocket medical expenditures and medical debt (including fewer bills sent to collection), and better self-reported physical and mental health than the control group.

The New York Times provided some of the details of the Medicaid success story:

Those with Medicaid were 35 percent more likely to go to a clinic or see a doctor, 15 percent more likely to use prescription drugs and 30 percent more likely to be admitted to a hospital. Researchers were unable to detect a change in emergency room use.

Women with insurance were 60 percent more likely to have mammograms, and those with insurance were 20 percent more likely to have their cholesterol checked. They were 70 percent more likely to have a particular clinic or office for medical care and 55 percent more likely to have a doctor whom they usually saw.

The insured also felt better: the likelihood that they said their health was good or excellent increased by 25 percent, and they were 40 percent less likely to say that their health had worsened in the past year than those without insurance.

As Ezra Klein of The Washington Post summed up the findings, "knowing that Medicaid matters is good, but we already sort of knew that."

It is also worth noting, as Klein does, that the Massachusetts analysis may understate the health care gains to all Americans, and not just the uninsured:

The national reforms, unlike the Massachusetts reforms, included major investments in comparative-effectiveness research, electronic health records, accountable care organizations and pay-for-quality pilots. If any or all of those initiatives pay off, they could dramatically improve our understanding of which treatments work and force the health-care system to integrate that new knowledge into everyday treatment decisions very quickly.

If that happens, medical care could become substantially more effective than it is now, which should also improve health outcomes. Quality improvements like that could, for the already insured, be the largest payoff from the Affordable Care Act.

Alas, those improvements have already carried a steep price for the Democratic Party and the cause of truth. As Jonathan Chait reported last week, a recent paper suggested (though not convincingly) that Democrats' support for the ACA cost them their House majority in November 2010. Meanwhile Republicans whipped up opposition with a torrent of lies about "death panels," a "government take-over of health care," added debt and "Medicaid ghettoes," and other smokescreens that continue to obscure the truth about President Obama's health care reform.

The truth, for starters, is that the Affordable Care Act is working.

(This piece also appears at Perrspectives.)