Kacie Kidd, University of Pittsburgh

It seems that more and more teens are identifying as transgender, gender-fluid or nonbinary.

But because linguistic and cultural norms are always evolving, it’s been challenging to pin down an exact number.

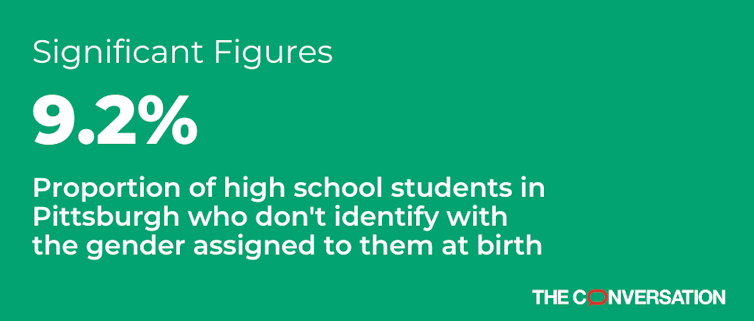

The 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, which was conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, found that 1.8% of high school students identified as transgender. But my team – made up of pediatricians, adolescent medicine specialists and public health researchers – suspected that this study underrepresented the prevalence of gender-diverse youth. That’s because not all people who are gender-diverse – an umbrella term for those whose gender identity does not fully align with the sex they were assigned at birth – identify as “transgender.”

So we put together a survey using more inclusive questions.

We asked high school students in Pittsburgh questions about their gender in two steps. First, we asked about their sex assigned at birth. Then we asked about their gender identity and allowed them to select the identities that applied to them.

Of the 3,168 teens who completed the questions, 9.2% had a gender identity that did not fully align with their sex assigned at birth. For example, someone assigned female at birth might identify with a gender other than “girl,” such as “nonbinary,” “boy” or “trans boy.”

This was a larger proportion than we’d seen in prior studies. Yet these more inclusive questions – which allowed us to identify anyone whose sex and gender identity did not fully align – may ultimately reflect the true prevalence of gender-diverse people.

There were some other notable findings.

For one, we also found that more teens of color expressed gender-diverse identities than their white counterparts. Yet the pediatric gender clinic where I work in Pittsburgh, like similar clinics across the United States, sees predominantly white patients.

Reasons for this pattern are not fully known, but we suspect that gender-diverse communities of color may have less access to medical specialists. They may also experience increased stigma and discrimination due to being both nonwhite and gender-diverse.

We also found that among the teens who identified as gender-diverse in our survey, more expressed a feminine or nonbinary identity, which doesn’t reflect the makeup of the patients seen in both our local clinic and in gender care clinics across the country, where patients tend to express masculine identities. This may be because trans women and girls – particularly trans women and girls of color – face higher rates of violence, and so may be less comfortable coming out and seeking care.

There are also mental health implications for these gender-diverse young people.

On average, teens with gender-diverse identities have higher rates of depression and thoughts of suicide compared to their peers who are cisgender, or identify with the sex they were assigned at birth.

This may be associated with gender dysphoria – the distress associated with the incongruence between sex assigned at birth and gender identity. However not all gender-diverse people have gender dysphoria.

My experience caring for this population of young people was supported by the numbers we saw in this survey: Gender-diverse teens exist – and in larger numbers than many people might realize. Their lives and experiences matter, and given the fact that they’re more vulnerable to mental health concerns, I believe equal access to compassionate, comprehensive health care becomes that much more crucial.

[Insight, in your inbox each day. You can get it with The Conversation’s email newsletter.]

![]()

Kacie Kidd, Pediatrician and Adolescent Medicine Fellow, University of Pittsburgh

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.