Morgan Bazilian, Colorado School of Mines; Deb Niemeier, University of Maryland; Edward R. Carr, Clark University; Kristie Ebi, University of Washington, and Walt Meier, NASA

The United States is formally back in the Paris climate agreement as of Feb. 19, 2021, nearly four years after former President Donald Trump announced it would pull out.

We asked five scholars what the U.S. rejoining the international agreement means for the nation and the rest of the world, including for food security, safety and the changing climate. Nearly every country has ratified the 2015 agreement, which aims to keep global temperature rise well below 2 degrees Celsius. The U.S. was the only one to withdraw.

What rejoining Paris means for America’s place in the world

Morgan Bazilian, Public Policy Professor and Director of the Payne Institute, Colorado School of Mines

Amanda Gorman, the National Youth Poet Laureate, wrote in her poem for U.S. President Joe Biden’s inauguration, “When day comes we step out of the shade.” That’s a good articulation of why the United States is now rejoining the Paris Agreement.

In the short term, the benefits are primarily diplomatic. It’s no small thing to try to rebuild international standing for a country that helped bring the world into the Paris Agreement and then abruptly abandoned it. Humility, acknowledging the nation’s recent abysmal record and reconsidering both the need for a U.S.-hosted climate summit and the habit of “naming and shaming” other countries could go a long way.

The Paris Agreement took years to design and develop. It allows for considerable flexibility and is inherently “bottom up” – each country sets its own goals and determines how it will live up to them. I was a negotiator in the climate talks for several years.

The agreement was never a threat. Its removal by the Trump administration was theater – or swagger. There will be temptation to hearken back to the policies and approaches of the Obama era – many of Biden’s political appointees come from that shared experience. Rejoining should be primarily used as an impetus for much more robust, stable, sustainable and thoughtful national policy and regulation. That’s the less glamorous stuff – the unfinished work.

Why US engagement matters for other countries

Edward Carr, Professor and Director of International Development, Community and Environment, Clark University

Just returning to the Paris Agreement as signed back in 2015 will not meet the world’s climate needs, nor will it restore the United States to a position of global leadership on climate change.

To gauge the seriousness of the Biden administration, other countries will be watching two things.

First, will the U.S. strengthen its commitments to decarbonizing the economy?

While the Trump administration worked to undermine global action on climate change, several states adopted aggressive targets, among them Washington, California and even states with Republican governors like Massachusetts. With targets that are much more ambitious than those agreed to by the United States under the 2015 Paris Agreement, these states make it clear that the U.S. can be much more aggressive in its national pledges without losing its global competitiveness.

Second, will the Biden administration invest heavily in adaptation at home and abroad?

A growing body of research shows that the worst impacts of climate change are borne by the poorest and most vulnerable people. Further, these impacts tend to exacerbate existing inequalities. The new administration has the tools. The world will have to see if its attention to justice and equality extends to the impacts of climate change.

A return to Paris is a good first step. But without additional steps, it will be seen as hollow and could further erode U.S. credibility.

What the Paris accord means for food security

Kristie Ebi, Professor of Global Health and Environment, University of Washington

Food security will be a theme of this century, in part because of rising carbon dioxide concentrations and our changing climate.

Globally, nearly 9% of the planet’s growing population is food insecure, with the numbers increasing over the past few years. About 45% of childhood deaths worldwide are attributable to insufficient calories or nutrients.

As the planet continues to warm, climate change threatens to make these situations worse.

The harm to crops as global temperatures rise isn’t just about heat, floods and droughts. While carbon dioxide is necessary for plant growth, research shows that rising CO2 concentrations will reduce the nutrient density of the world’s two most important crops, wheat and rice, as well as other food sources. These nutritional losses can have serious health effects, including impaired cognitive development and metabolism, obesity and diabetes.

Further, the climatic changes resulting from rising CO2 are reducing crop yields and the stability of the food supply.

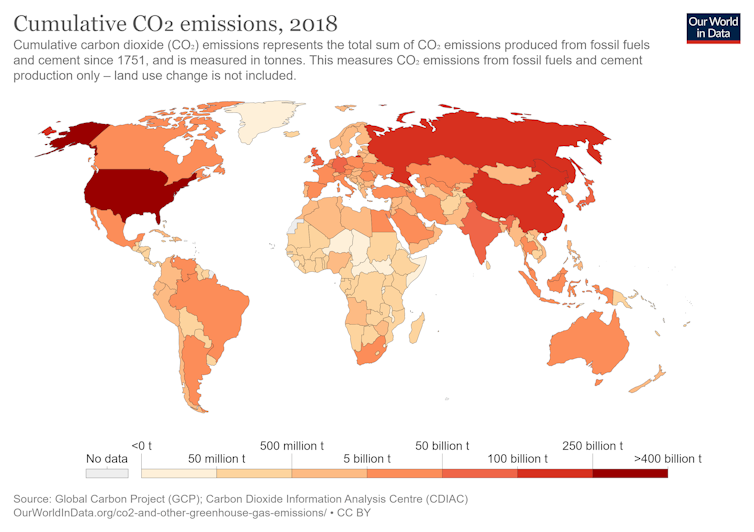

The U.S. is the second-largest CO2 emitter after China, and the largest historically. The Biden administration’s recommitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions under the Paris climate agreement and advance research and development for solutions can help protect the health and well-being of families and future generations.

Why the Paris accord matters for vulnerable communities

Deb Niemeier, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Maryland

In a valley once home to the Maidu tribes, local legend has it that a man stood on a ridge in the 1860s, escaping the heat of the central valley of California. Basking in the cool air, he was certain he had found paradise. For the next 50-some years, that ridge saw mining give way to timber mills and eventually the planting of fruit orchards. A small but sturdy town grew, along the way weathering many fires.

Over time, Paradise, California, became home to farmers, retired people and others just seeking a quieter life. The air was crisp and the vistas extraordinary. The Camp Fire of 2018 destroyed nearly the entire town and devastated many of its farms. I was there afterward. The culprit was both aging infrastructure and extremely dry conditions that have become more common as the planet warms.

The future of humanity has always been intertwined with that of the natural world. Today, however, people have an outsize influence that comes in part from years of burning fossil fuels and other activities that influence the climate.

Coastal communities are facing more frequent flooding as sea level rises. Western wildfire seasons are lasting longer. The National Climate Assessment has shown how extreme storms and health- and crop-harming heat waves will become more common as global temperatures rise.

Just fixing faulty power lines that can spark wildfires isn’t enough anymore. The Paris Agreement motivates countries to start the hard work of reducing greenhouse gas emissions to lower the underlying risk.

Paris and the problem of a fast-warming Arctic

Walt Meier, Senior Research Scientist, National Snow and Ice Data Center, University of Colorado

The importance of the Paris climate agreement is particularly evident in the Arctic, where sea ice is diminishing and permafrost is thawing. If you think about the implications for the entire planet, your imagination needs to expand threefold. That’s because the Arctic is warming nearly three times as fast as the global average.

A large part of the Arctic’s climate sits on a knife’s edge between freezing and melting. Even a small change can have big consequences. An increase of 2 degrees Fahrenheit in the midlatitudes, say from 70 F to 72 F, is not easily noticed. But in the Arctic Ocean, a 2-degree change, from 31 F to 33 F, is the difference between ice skating and swimming.

That change from ice to ocean, and from snow to bare ground, is profound. Ice and snow are white, which means they reflect most of the sun’s energy, keeping the Arctic cool. Losing the ice and snow means more sunlight is absorbed, which further warms the Earth and causes even more melting.

So, every bit of greenhouse gas emitted has triple the punch in the Arctic that it does in lower latitudes. This means that every bit of greenhouse gas that the Paris climate agreement can help countries avoid emitting saves it times three in the Arctic.

Our choices influence the fate of the Arctic – and the world.

This article has been updated with the U.S. formally returning to the Paris Agreement.

[Expertise in your inbox. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

![]()

Morgan Bazilian, Professor of Public Policy and Director, Payne Institute, Colorado School of Mines; Deb Niemeier, Clark Distinguished Chair and Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Maryland; Edward R. Carr, Professor and Director, International Development, Community, and Environment, Clark University; Kristie Ebi, Professor of Global Health and Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences, University of Washington, and Walt Meier, Senior Research Scientist, National Snow and Ice Data Center, NASA

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.