Nick Lehr/The Conversation via Jasperdo, CC BY-NC-ND

Michael J. Socolow, University of Maine

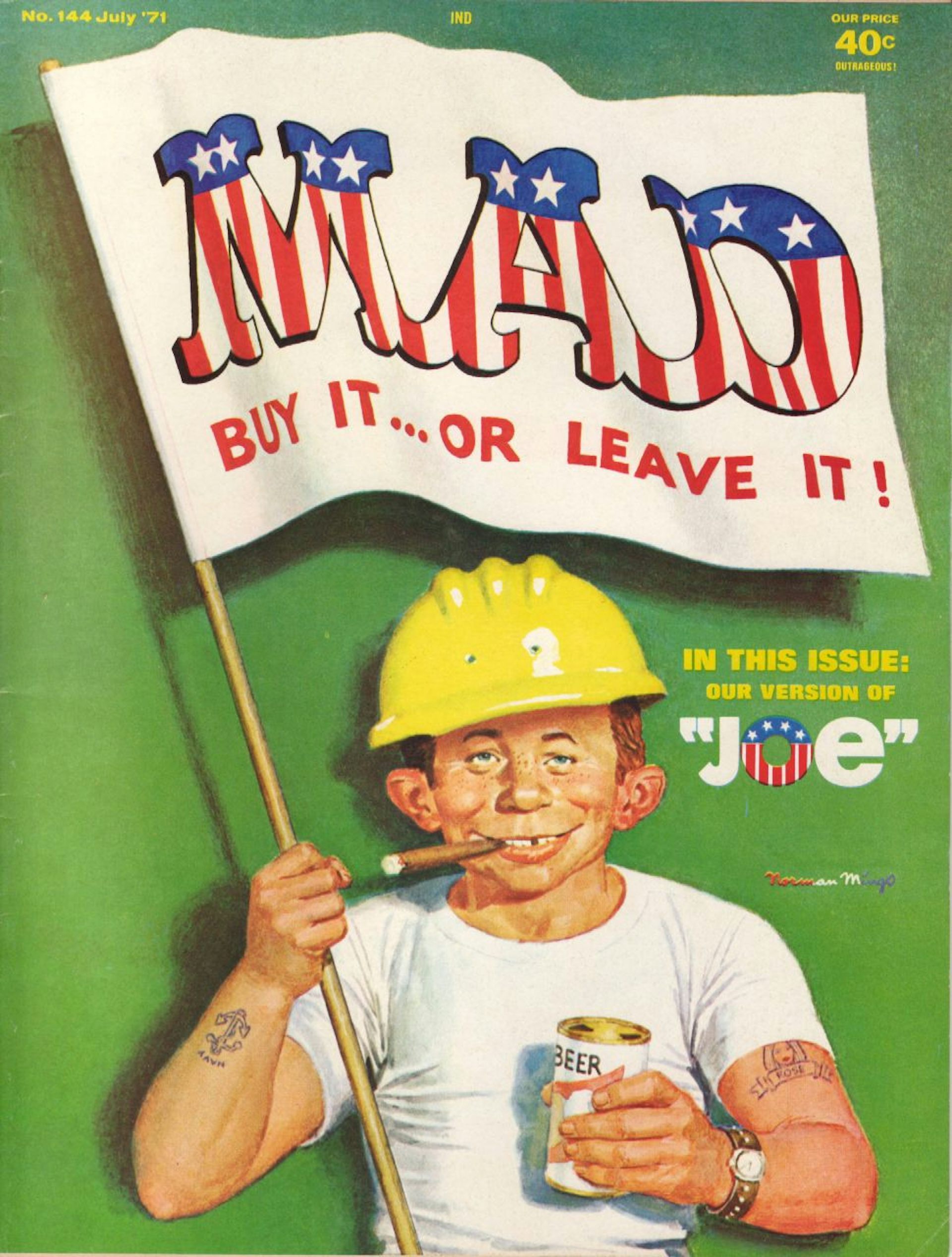

Mad Magazine is on life support. In April 2018, it launched a reboot, jokingly calling it its “first issue.” Now the magazine announced it will stop publishing new content, aside from year-end special issues.

But in terms of cultural resonance and mass popularity, its clout has been fading for years.

At its apex in the early 1970s, Mad’s circulation surpassed 2 million. As of 2017, it was 140,000.

As strange as it sounds, I believe the “usual gang of idiots” that produced Mad was performing a vital public service, teaching American adolescents that they shouldn’t believe everything they read in their textbooks or saw on TV.

Mad preached subversion and unadulterated truth-telling when so-called objective journalism remained deferential to authority. While newscasters regularly parroted questionable government claims, Mad was calling politicians liars when they lied. Long before responsible organs of public opinion like The New York Times and the CBS Evening News discovered it, Mad told its readers all about the credibility gap. The periodical’s skeptical approach to advertisers and authority figures helped raise a less credulous and more critical generation in the 1960s and 1970s.

Today’s media environment differs considerably from the era in which Mad flourished. But it could be argued that consumers are dealing with many of the same issues, from devious advertising to mendacious propaganda.

While Mad’s satiric legacy endures, the question of whether its educational ethos – its implicit media literacy efforts – remains part of our youth culture is less clear.

A merry-go-round of media panics

In my research on media, broadcasting and advertising history, I’ve noted the cyclical nature of media panics and media reform movements throughout American history.

The pattern goes something like this: A new medium gains popularity. Chagrined politicians and outraged citizens demand new restraints, claiming that opportunists are too easily able to exploit its persuasive power and dupe consumers, rendering their critical faculties useless. But the outrage is overblown. Eventually, audience members become more savvy and educated, rendering such criticism quaint and anachronistic.

During the penny press era of the 1830s, periodicals often fabricated sensational stories like the “Great Moon Hoax” to sell more copies. For a while, it worked, until accurate reporting became more valuable to readers.

When radios became more prevalent in the 1930s, Orson Welles perpetrated a similar extraterrestrial hoax with his infamous “War of the Worlds” program. This broadcast didn’t actually cause widespread fear of an alien invasion among listeners, as some have claimed. But it did spark a national conversation about radio’s power and audience gullibility.

Aside from the penny newspapers and radio, we’ve witnessed moral panics about dime novels, muckraking magazines, telephones, comic books, television, the VCR, and now the internet. Just as Congress went after Orson Welles, we see Mark Zuckerberg testifying about Facebook’s facilitation of Russian bots.

Holding up a mirror to our gullibility

But there’s another theme in the country’s media history that’s often overlooked. In response to each new medium’s persuasive power, a healthy popular response ridiculing the rubes falling for the spectacle has arisen.

For example, in “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” Mark Twain gave us the duke and the dauphin, two con artists traveling from town to town exploiting ignorance with ridiculous theatrical performances and fabricated tall tales.

They were proto-purveyors of fake news, and Twain, the former journalist, knew all about selling buncombe. His classic short story “Journalism in Tennessee” excoriates crackpot editors and the ridiculous fiction often published as fact in American newspapers.

Then there’s the great P.T. Barnum, who ripped people off in marvelously inventive ways.

“This way to the egress,” read a series of signs inside his famous museum. Ignorant customers, assuming the egress was some sort of exotic animal, soon found themselves passing through the exit door and locked out.

They might have felt ripped off, but, in fact, Barnum had done them a great – and intended – service. His museum made its customers more wary of hyperbole. It employed humor and irony to teach skepticism. Like Twain, Barnum held up a funhouse mirror to America’s emerging mass culture in order to make people reflect on the excesses of commercial communication.

‘Think for yourself. Question authority’

Mad Magazine embodies this same spirit. Begun originally as a horror comic, the periodical evolved into a satirical humor outlet that skewered Madison Avenue, hypocritical politicians and mindless consumption.

Teaching its adolescent readers that governments lie – and only suckers fall for hucksters – Mad implicitly and explicitly subverted the sunny optimism of the Eisenhower and Kennedy years. Its writers and artists poked fun at everyone and everything that claimed a monopoly on truth and virtue.

“The editorial mission statement has always been the same: ‘Everyone is lying to you, including magazines. Think for yourself. Question authority,’” according to longtime editor John Ficarra.

That was a subversive message, especially in an era when the profusion of advertising and Cold War propaganda infected everything in American culture. At a time when American television only relayed three networks and consolidation limited alternative media options, Mad’s message stood out.

Just as intellectuals Daniel Boorstin, Marshall McLuhan and Guy Debord were starting to level critiques against this media environment, Mad was doing the same – but in a way that was widely accessible, proudly idiotic and surprisingly sophisticated.

For example, the implicit existentialism hidden beneath the chaos in every “Spy v. Spy” panel spoke directly to the insanity of Cold War brinksmanship. Conceived and drawn by Cuban exile Antonio Prohías, “Spy v. Spy” featured two spies who, like the United States and the Soviet Union, both observed the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction. Each spy was pledged to no one ideology, but rather the complete obliteration of the other – and every plan ultimately backfired in their arms race to nowhere.

The cartoon highlighted the irrationality of mindless hatred and senseless violence. In an essay on the plight of the Vietnam War soldier, literary critic Paul Fussell once wrote that U.S. soldiers were “condemned to sadistic lunacy” by the monotony of violence without end. So too the “Spy v. Spy” guys.

As the credibility gap widened from the Johnson to Nixon administrations, the logic of Mad‘s Cold War critique became more relevant. Circulation soared. Sociologist Todd Gitlin – who had been a leader of the Students for a Democratic Society in the 1960s – credited Mad with serving an important educational function for his generation.

“In junior high and high school,” he wrote, “I devoured it.”

A step backward?

And yet that healthy skepticism seems to have evaporated in the ensuing decades. Both the run-up to the Iraq War and the acquiescence to the carnival-like coverage of our first reality TV star president seem to be evidence of a widespread failure of media literacy.

We’re still grappling with how to deal with the internet and the way it facilitates information overload, filter bubbles, propaganda and, yes, fake news.

But history has shown that while we can be stupid and credulous, we can also learn to identify irony, recognize hypocrisy and laugh at ourselves. And we’ll learn far more about employing our critical faculties when we’re disarmed by humor than when we’re lectured at by pedants. A direct thread skewering the gullibility of media consumers can be traced from Barnum to Twain to Mad to “South Park” to The Onion.

While Mad’s legacy lives on, today’s media environment is more polarized and diffuse. It also tends to be far more cynical and nihilistic. Mad humorously taught kids that adults hid truths from them, not that in a world of fake news, the very notion of truth was meaningless. Paradox informed the Mad ethos; at its best, Mad could be biting and gentle, humorous and tragic, and ruthless and endearing – all at the same time.

That’s the sensibility we’ve lost. And it’s why we need outlets like Mad more than ever.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on May 11, 2018.

![]()

Michael J. Socolow, Associate Professor, Communication and Journalism, University of Maine

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.