Derrick P. Alridge, University of Virginia

As a historian who studies W.E.B. Du Bois – and as someone who once lived in nearby Athens, Georgia – I’m struck by the significance of Atlanta hosting the Super Bowl at this moment in the country’s history.

When Du Bois lived in Atlanta in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was a place of both opportunity and peril for blacks. During the civil rights era, it headquartered the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, while serving as a base for black student activism. Today, many view it as America’s “Black Mecca.” It has a solid black middle and upper class, possesses a vibrant soul and hip-hop music scene and serves as a base of black political power.

Atlanta hosting the Super Bowl, however, creates an undeniable paradox.

Over the past few seasons, the NFL has found itself grappling with the issue of whether to allow its players to protest the killings of unarmed black men and women by kneeling during the national anthem. The league has made clear that it doesn’t support players’ right to protest, and many of the Americans who cheer for these players every Sunday object to those same players standing up against the racial inequalities that persist in American life.

While much of the focus of Sunday’s game will be on the pageantry and competition, I think it’s worth reflecting on how Atlanta evolved into the city it is today, the forces that threaten its progress, and how hosting the Super Bowl symbolizes this tension.

Two Atlantas, two warring ideals

In 1897, Du Bois came to Atlanta to establish a center of social scientific research at Atlanta University. During this time in Du Bois’ life, Atlanta was ground zero for America’s racial tensions. It was strictly segregated and subject to Jim Crow laws, and 241 blacks were lynched in Georgia between 1888 and 1903.

In 1899, Du Bois lost his infant son, Burghardt, to diphtheria, a bacterial infection. Du Bois believed Burghardt died from a lack of prompt treatment because white doctors in Atlanta would not treat black patients. That same year, a black man named Sam Hose was brutally lynched in nearby Newnan, Georgia, after being accused of raping a white woman.

These two events tremendously influenced Du Bois, his relationship with Atlanta, and his understanding of race in America. In 1903, he published “The Souls of Black Folk,” in which he declared, “the problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color-line.”

Du Bois foresaw a future in which black Americans would endure the “psychic tension” of living in a society that encouraged them to be Americans yet condemned them to second-class citizenship.

“One ever feels his two-ness,” he wrote, “an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

Following the book’s publication, Du Bois continued to face challenges in Atlanta. In 1906, riots broke out after a local paper published rumors of black men raping white women. In response, Du Bois penned the poem “A Litany of Atlanta,” petitioning God for understanding and intervention.

“A city lay in travail, God our Lord, and from her loins sprang twin Murder and Black Hate,” he wrote.

Despite his grief, Du Bois held out hope that Atlanta, the “city of a hundred hills,” could become a beacon of greater democracy.

Of Atalanta and golden apples

In “The Souls of Black Folk,” Du Bois also draws on Greek mythology to recount the legend of the “winged maiden” Atalanta, who, disinclined to marry, says she will only marry a man who can beat her in a foot race. When a suitor, Hippomenes, challenges Atalanta, he lures her off course with three golden apples. Atalanta’s greed costs her the race and she is forced to marry Hippomenes.

The story is a cautionary one. For Du Bois, Atlanta had the potential to be a great city. But if it worshiped materialism and chased wealth, it too would suffer the curse of Atalanta. Instead of reaching for golden apples, Du Bois encouraged Atlanta to establish and support universities that promote democratic ideals of “truth,” “freedom” and “broad humanity,” while striving to “Teach thinkers to think.”

In many ways, Atlanta has lived up to Du Bois’ dreams for the city. Today, it is home to the vibrant Atlanta University Center Consortium, which comprises Clark Atlanta University, Morehouse, Spelman and Morehouse School of Medicine; Atlanta, along with Washington, D.C., is considered by Forbes as the best U.S. city economically for blacks; and Keisha Lance Bottoms serves as the city’s seventh consecutive black mayor.

Yet, as historian Maurice Hobson has pointed out, Atlanta also has a large percentage of its black population living in poverty. At certain points over the past five years, 80 percent of black children in Atlanta resided in poverty-ridden communities and unemployment among blacks has been as high as 22 percent.

There is still work to be done, and golden apples can be tempting. According to the Metro Atlanta Chamber, the Super Bowl will reportedly have a US$400 million economic impact on the city. While attracting revenue can be beneficial, the city has already lost of some its legacy as a result of development.

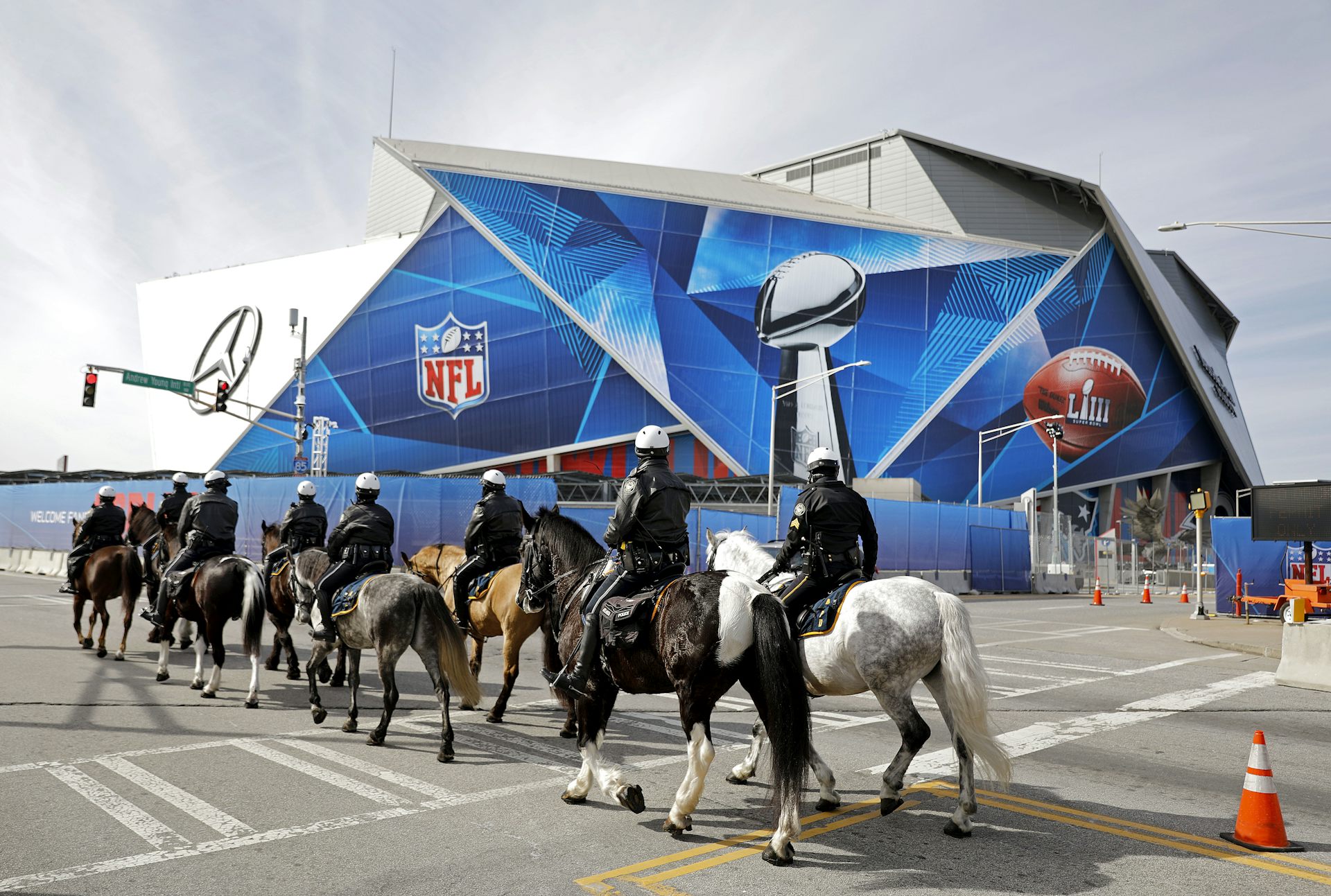

In fact, the $1.5 billion Mercedes-Benz Stadium, where the Super Bowl will be held, sits on the grounds of the historic Friendship and Mount Vernon Baptist churches – a symbol of how the forces of development can silence history and wipe out communities.

What to watch for

Du Bois’ ideas in “The Souls of Black Folk” provide a framework for understanding the complexities of the Super Bowl taking place in Atlanta.

While black players are lauded for their on-field accomplishments, the harsh criticism they receive for peacefully protesting racial inequality creates the double consciousness Du Bois so eloquently described. It raises, again, a question Du Bois famously posed: “How does it feel to be a problem? I answer seldom a word.”

Will the Super Bowl organizers showcase Atlanta’s civil rights history, or gloss over it? Will they bring attention to the city’s rich legacy of peacefully protesting racial injustice? I’m not getting my hopes up.

As I watch the halftime show, I will appreciate singer Rihanna’s refusal to participate; I’ll also be thinking about Jay-Z’s decision not to perform at last year’s Super Bowl, reportedly in support of players’ peaceful protests.

Despite the paradox of hosting the Super Bowl, the city does seem to understand that this is an important opportunity to provide the nation with a teachable moment.

Last year, city officials launched an initiative to paint murals around the city to commemorate the civil rights movement in the months leading up to the Super Bowl. In addition, the NAACP and other civil rights groups will hold a protest on the day before the Super Bowl.

I hope that this tradition will continue – that, in the long run, Atlanta will resist the temptation to be enticed by Hippomenes’ golden apples, that it will bring attention to racial injustices by advocating for “truth,” “freedom” and “humanity.”

Derrick P. Alridge, Professor of Education, University of Virginia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.