Stacy A. Cordery, Iowa State University

No one doubts the job of president of the United States is stressful and demanding. The chief executive deserves downtime.

But how much is enough, and when is it too much?

These questions came into focus after Axios’ release of President Donald Trump’s schedule. The hours blocked off for nebulous “executive time” seem, to many critics, disproportionate to the number of scheduled working hours.

While Trump’s workdays may ultimately prove to be shorter than those of past presidents, he’s not the first to face criticism. For every president praised for his work ethic, there’s one disparaged for sleeping on the job.

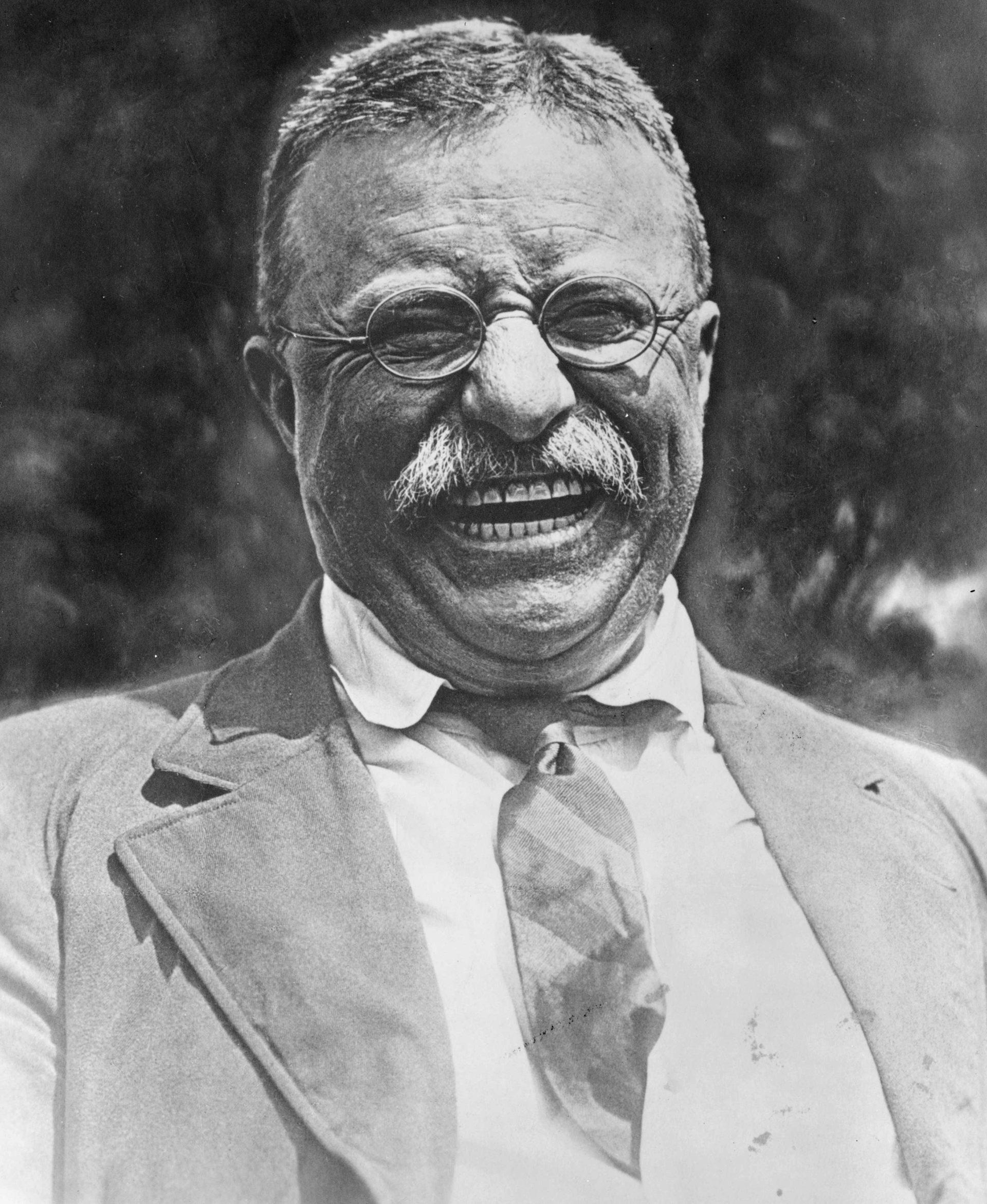

Teddy Roosevelt, locomotive president

Before Theodore Roosevelt ascended to the presidency in 1901, the question of how hard a president toiled was of little concern to Americans.

Except in times of national crisis, his predecessors neither labored under the same expectations, nor faced the same level of popular scrutiny. Since the country’s founding, Congress had been the main engine for identifying national problems and outlining legislative solutions. Congressmen were generally more accessible to journalists than the president was.

But when Roosevelt shifted the balance of power from Congress to the White House, he created the expectation that an activist president, consumed by affairs of state, would work endlessly in the best interests of the people.

Roosevelt, whom Sen. Joseph Foraker called a “steam engine in trousers,” personified the hard-working chief executive. He filled his days with official functions and unofficial gatherings. He asserted his personality on policy and stamped the presidency firmly on the nation’s consciousness.

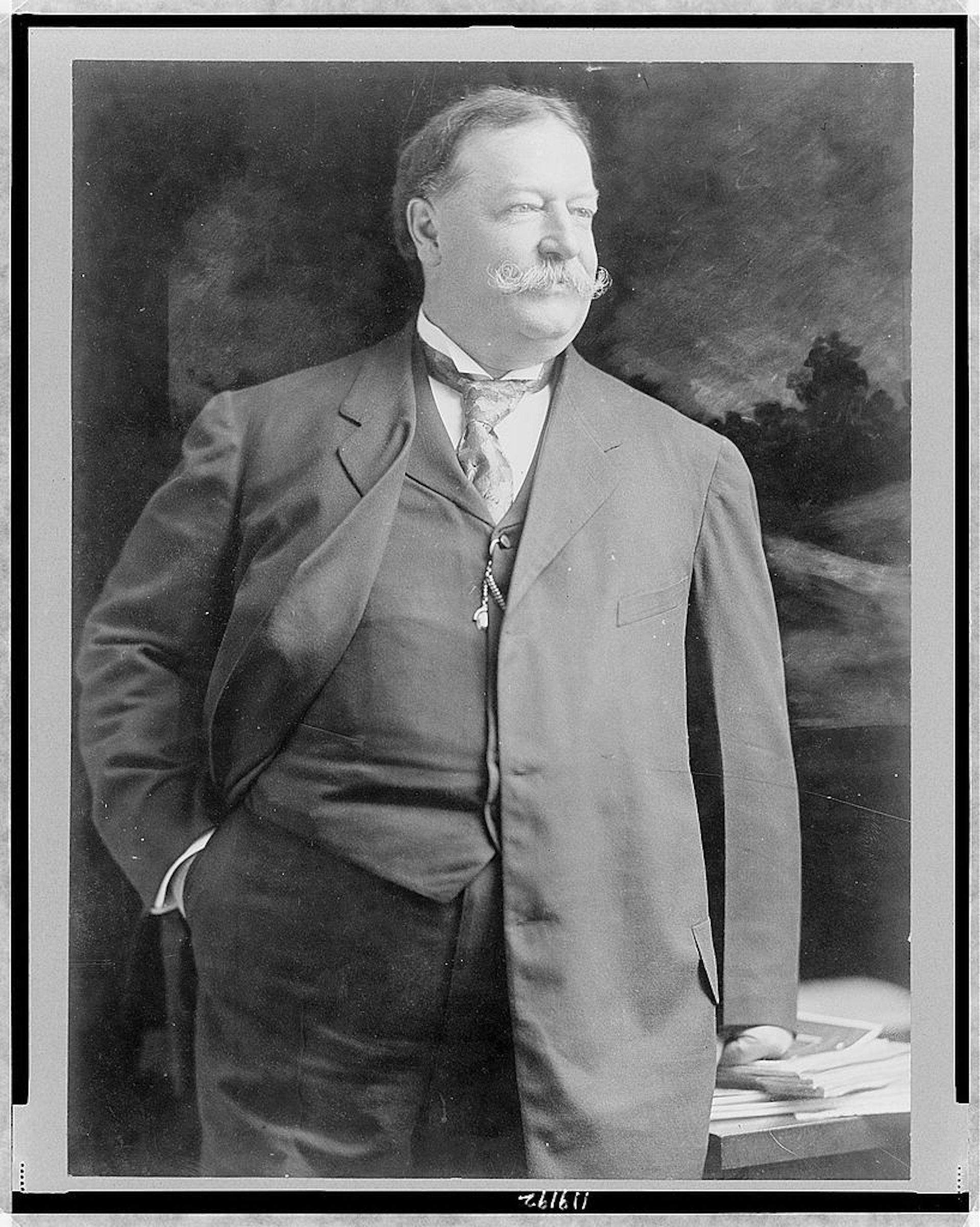

Taft had a tough act to follow

His successor, William Howard Taft, suffered by comparison. While it’s fair to observe that nearly anyone would have looked like a slacker compared with Roosevelt, it didn’t help that Taft weighed 300 pounds, which his contemporaries equated with laziness.

Taft helped neither his cause nor his image when he snored through meetings, at evening entertainments and, as author Jeffrey Rosen noted, “even while standing at public events.” Watching Taft’s eyelids close, Sen. James Watson said to him, “Mr. President, you are the largest audience I ever put entirely to sleep.”

An early biographer called Taft “slow-moving, easy-going if not lazy” with “a placid nature.” Others have suggested that Taft’s obesity caused sleep apnea and daytime drowsiness, a finding not inconsistent with historian Lewis L. Gould’s conclusion that Taft was capable of work “at an intense pace” and “a high rate of efficiency.”

It seems that Taft could work quickly, but in short bursts.

Coolidge the snoozer

Other presidents were more intentional about their daytime sleeping. Calvin Coolidge’s penchant for hourlong naps after lunch earned him amused scorn from contemporaries. But when he missed his nap, he fell asleep at afternoon meetings. He even napped on vacation. Tourists stared in amazement as the president, blissfully unaware, swayed in a hammock on his front porch in Vermont.

This, for many Republicans, wasn’t a problem: The Republican Party of the 1920s was averse to an activist federal government, so the fact that Coolidge wasn’t seen as a hard-charging, incessantly busy president was fine.

Biographer Amity Shlaes wrote that “Coolidge made a virtue of inaction” while simultaneously exhibiting “a ferocious discipline in work.” Political scientist Robert Gilbert argued that after Coolidge’s son died during his first year as president, Coolidge’s “affinity for sleep became more extreme.” Grief, according to Gilbert, explained his growing penchant for slumbering, which expanded into a pre-lunch nap, a two- to four-hour post-lunch snooze and 11 hours of shut-eye nightly.

For Reagan, the jury’s out

Ronald Reagan may have had a tendency to nod off.

“I have left orders to be awakened at any time in case of a national emergency – even if I’m in a cabinet meeting,” he joked. Word got out that he napped daily, and historian Michael Schaller wrote in 1994 that Reagan’s staff “released a false daily schedule that showed him working long hours,” labeling his afternoon nap “personal staff time.” But some family members denied that he napped in the White House.

Journalists were divided. Some found him “lazy, passive, stupid or even senile” and “intellectually lazy … without a constant curiosity,” while others claimed he was “a hard worker,” who put in long days and worked over lunch. Perhaps age played a role in Reagan’s naps – if they happened at all.

Clinton crams in the hours

One president not prone to napping was Bill Clinton. Frustrated that he could not find time to think, Clinton ordered a formal study of how he spent his days. His ideal was four hours in the afternoon “to talk to people, to read, to do whatever.” Sometimes he got half that much.

Two years later, a second study found that, during Clinton’s 50-hour workweek, “regularly scheduled meetings” took up 29 percent of his time, “public events, etc.” made up 36 percent of his workday, while “thinking time – phone & office work” constituted 35 percent of his day. Unlike presidents whose somnolence drew sneers, Clinton was disparaged for working too much and driving his staff to exhaustion with all-nighters.

Partisanship at the heart of criticism?

The work of being president of the United States never ends. There is always more to be done. Personal time may be a myth, as whatever the president reads, watches or does can almost certainly be applied to some aspect of the job.

Trump’s “executive time” could be a rational response to the demands of the job or life circumstances. Trump, for example, only seems to get four or five hours of sleep a night, which seems to suggest that he has more time to tackle his daily duties than the rest of us.

But, like his predecessors, the appearance of taking time away from running the country will garner criticism. Though they can sometimes catch 40 winks, presidents can seldom catch a break.

Stacy A. Cordery, Professor of History, Iowa State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.