Cassandra Moseley, University of Oregon

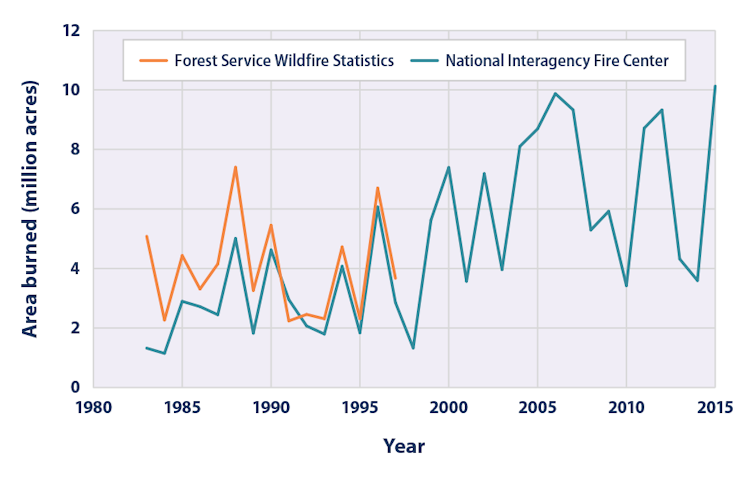

Hopes for fewer large wildfires in 2018, after last year’s disastrous fire season, are rapidly disappearing across the West. Six deaths have been reported in Northern California’s Carr Fire, including two firefighters. Fires have scorched Yosemite, Yellowstone, Crater Lake, Sequoia and Grand Canyon national parks. A blaze in June forced Colorado to shut down the San Juan National Forest. So far this year, 4.6 million acres have burned nationwide – less than last year, but well above the 10-year average of 3.7 million acres at this date.

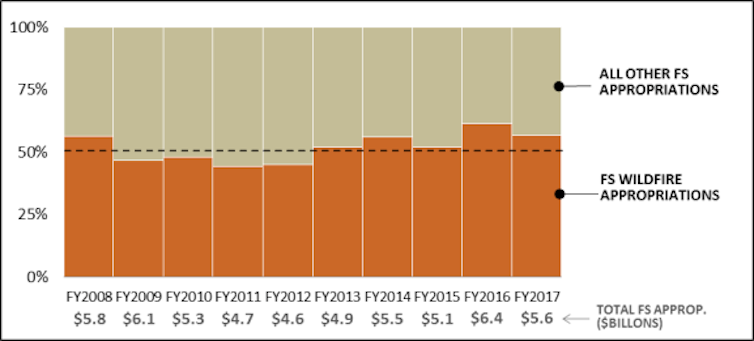

These active wildfire years also mean higher firefighting costs. For my research on natural resource management and rural economic development, I work frequently with the U.S. Forest Service, which does most federal firefighting. Rising fire suppression costs over the past three decades have nearly destroyed the agency’s budget. Its overall funding has been flat for decades, while fire suppression costs have grown dramatically.

Earlier this year Congress passed a “fire funding fix” that changes the way in which the federal government will pay for large fires during expensive fire seasons. But it doesn’t affect the factors that are making fire suppression more costly, such as climate trends and more people living in fire prone landscapes.

More burn days, more fuel

What is driving this trend? Many factors have come together to create a perfect storm. They include climate change, past forest and fire management practices, housing development, increased focus on community protection and the professionalization of wildfire management.

Fire seasons are growing longer in the United States and worldwide. According to the Forest Service, climate change has expanded the wildfire season by an average of 78 days per year since 1970. This means agencies need to keep seasonal employees on their payrolls longer and have contractors standing by earlier and available to work later in the year. All of this adds to costs, even in low fire years.

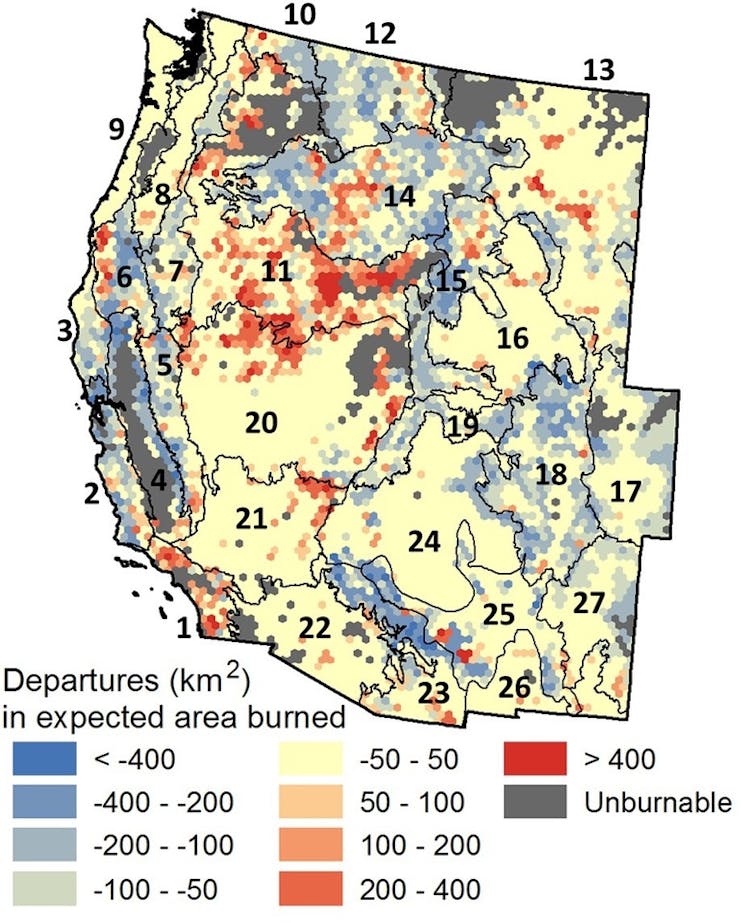

In many parts of the wildfire-prone West, decades of fire suppression combined with historic logging patterns have created small, dense forest stands that are more vulnerable to large wildfires. In fact, many areas have fire deficits – significantly less fire than we would expect given current climatic and forest conditions. Fire suppression in these areas only delays the inevitable. When fires do get away from firefighters, they are more severe because of the accumulation of small trees and brush.

Protecting communities and forests

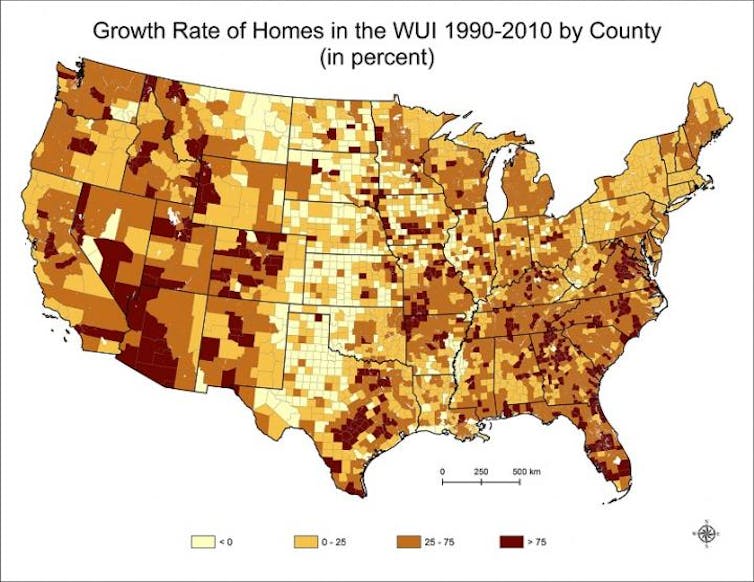

In recent decades, development has pushed into areas with fire-prone ecosystems – the wildland-urban interface. In response, the Forest Service has shifted its priorities from protecting timber resources to trying to keep fire from reaching houses and other physical infrastructure.

Fires near communities are fraught with political pressure and complex interactions with state and local fire and public safety agencies. They put enormous pressure on the Forest Service to do whatever is possible to suppress fires. There is considerable impetus to use air tankers and helicopters, although these resources are expensive and only effective in a limited number of circumstances.

As it started to prioritize protecting communities in the late 1980s, the Forest Service also ended its policy of fully suppressing all wildfires. Now fires are managed using a multiplicity of objectives and tactics, ranging from full suppression to allowing fires to grow larger so long as they stay within desired ranges.

This shift requires more and better-trained personnel and more interagency coordination. It also means letting some fires grow bigger, which requires personnel to monitor the blazes even when they stay within acceptable limits. Moving away from full suppression and increasing prescribed fire is controversial, but many scientists believe it will produce long-term ecological, public safety and financial benefits.

Professionalizing wildfire response

As fire seasons lengthened and staffing for the national forest system declined, the Forest Service was less and less able to use national forest employees as a militia whose regular jobs could be set aside for brief periods for firefighting. Instead, it started to hire staff dedicated exclusively to wildfire management and use private-sector contractors for fire suppression.

There is little research on the costs of this transition, but hiring more dedicated professional fire staffers and a large contractor pool is probably more expensive than the Forest Service’s earlier model. However, as the agency’s workforce shrank by 20,000 between 1980 and the early 2010s and fire seasons expanded, it had little choice but to transform its fire organization.

Baked-in fire risks

Many of these drivers are beyond the Forest Service’s control. Climate change, the fire deficit on many western lands and development in the wildland-urban interface ensure that the potential for major fires is baked into the system for decades to come.

There are some options for reducing risks and managing costs. Public land managers and forest landowners may be able to influence fire behavior in certain settings with techniques such as hazardous fuels reduction and prescribed fire. But these strategies will further increase costs in the short and medium term.

Another cost-saving strategy would be to rethink how firefighters use expensive resources such as airplanes and helicopters. But it will require political courage for the Forest Service to not use expensive resources on high-profile wildfires when they may not be effective.

Even if these approaches work, they will likely only slow the rate of increase in costs. Wildfire fighting costs now consume more than half of the agency’s budget. This is a problem because it reduces funds for national forest management, research and development, and support for state and private forestry. Over the long term, these are the very activities that are needed to address the growing problem of wildfire.

![]() This is an updated version of an article originally published July 25, 2018.

This is an updated version of an article originally published July 25, 2018.

Cassandra Moseley, Associate Vice President for Research and Research Professor, University of Oregon

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.