Brian Galle, Georgetown University

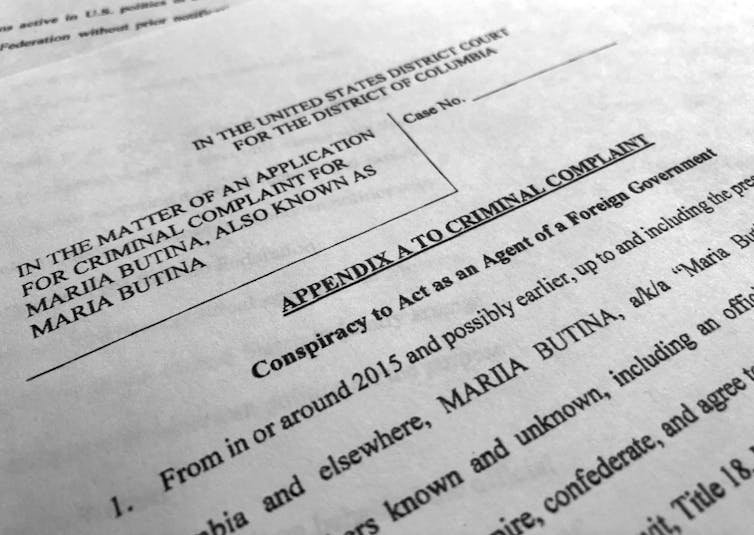

Editor’s note: U.S. authorities have arrested Mariia Butina, a Russian advocate for firearms ownership also known as Maria. In a criminal complaint that led to her indictment, the Justice Department accused her of secretly infiltrating American electoral politics as a foreign agent working on behalf of Russia and engaged in an anti-U.S. conspiracy. Numerous media reports allege that Butina illegally helped funnel Russian money into Donald Trump’s presidential campaign through the National Rifle Association. Brian Galle, a law professor who used to work for the Justice Department, explains what the consequences might be if the charges and accounts are true.

1. How could the government punish the organization?

The court papers allude to the NRA, although not by name. Several news sources have described in detail the relationship Butina and her Russian employer built with the organization, starting in 2013 or earlier. Depending on what NRA officials knew and when they knew it, the government could make a case that the gun advocacy and lobby group coordinated with Butina to help her advance Russian interests here in the U.S. – making it a co-conspirator in her individual lawbreaking.

The NRA has several arms. Its largest operation is technically known as a social welfare group or 501(c)(4) organization, granting it exemption from U.S. taxes. Another branch is a traditional charitable organization, making contributions to that entity tax deductible. Under federal tax law, when either of these kinds of nonprofits break laws, they jeopardize their tax exempt status.

The government has stripped several nonprofits of their tax exemptions for breaking the law over the years, including organizations that used their charitable status to defraud donors and, in the 1940s and ‘50s, groups suspected of supporting communism.

Some media reports suggest the NRA served as a conduit for Russian money that landed in the Trump presidential campaign’s coffers. If that proves true, it would violate election laws that bar foreigners from funding political candidates. At the same time, however, there could be some ways to structure such transactions as technically legal, as dark money expert Robert Maguire notes.

In addition, many state and federal laws treat the use of fake or “straw donors” to make campaign contributions with someone else’s money as a crime, punishable with fines. Conceivably, there could be individual criminal liability, even jail time, for any NRA leaders who might be found guilty of scheming to misreport campaign expenditures.

But, I want to emphasize, nothing in the court papers unsealed on July 16, 2018, support those scenarios.

2. What might happen to its influence?

Since charitable giving tends to be an emotional act, some donors might not continue to support the NRA if it lands in legal trouble. Past scandals have weakened support for other prominent nonprofits, such as the Wounded Warrior Project.

For an organization that has cast itself as a bulwark of patriotism, any evidence that it conspired to undermine U.S. laws seems off-brand. On the other hand, polls indicate that support for Vladimir Putin has soared among Republicans, making it hard to predict how the NRA’s members and big donors might respond.

Public scrutiny might also make the NRA more cautious in how it doles out its political spending, a major source of its influence these days. The organization spent more than $30 million supporting President Trump alone in 2016, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. If its benefactors become more suspect, even among the NRA’s base, that could loosen its grip over many American politicians and policymakers.

3. How might the government catch more of these alleged infractions?

Although U.S. charities can’t engage in political spending, they are allowed to partner with social welfare groups, as the NRA and the NRA Foundation do.

Unlike charities, social welfare groups can lobby, and they are allowed to spend at least some of their budget on election-related activity. Their donors are known to the government, but hidden from the public, which is why their funding is sometimes called “dark money.”

And the Trump administration just made dark money darker.

Just hours after the government announced Butina’s arrest, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin declared that the IRS was reducing the reporting requirements for donations to social welfare groups. Under this new guidance, 501(c)(4) groups will no longer need to reveal most of their donations on their tax returns, even to the IRS.

![]() In my opinion, it’s hard to see this move as anything except an effort to help big-money donors cover their tracks. Without a list of donors, the IRS can’t know when an organization is being used to further the interests of those backers, instead of the public.

In my opinion, it’s hard to see this move as anything except an effort to help big-money donors cover their tracks. Without a list of donors, the IRS can’t know when an organization is being used to further the interests of those backers, instead of the public.

Brian Galle, Professor of Law, Georgetown University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.